After over 40 years of searching, the story of the Atlas family while enslaved has been unearthed, uncovering ties to the family of President Andrew Jackson.

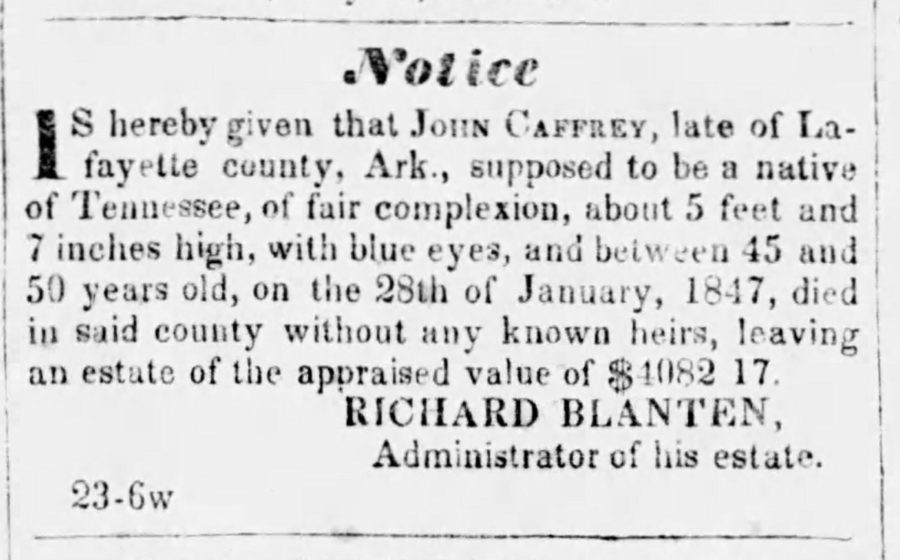

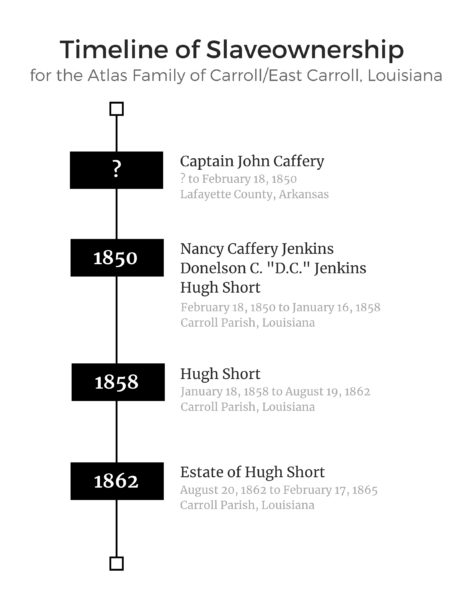

In 1847, John Caffery, Jr., a ferry operator and slaveholder, died a single man in Lafayette County, Arkansas . He was 52 years old. Identifying his next of kin should have been easy, but William Richard Blanton, an associate and neighbor of Caffery, could not live up to the task. As administrator of Caffery’s estate, Blanton tried valiantly to locate heirs to Caffery’s property – nearly 190 acres of land, a thriving ferry business on the Red River, and five enslaved people – but his efforts came up short. As a last resort he published a notice in the Washington Telegraph on May 19, 1847, almost four months after Caffery passed away. The blond haired, blue eyed Caffery was gone from this earth, but his possessions lay in wait for distribution.

It’s an emotional rollercoaster for a family – who before the law were counted as three fifths a person yet lived, breathed, and emoted like the other humans who claimed ownership over them – to be in legislative limbo. Before Caffery’s death it was just King Atlas, Sr., his wife, Rachel Day, Rachel’s son Henry, and their sons John, and King Jr. But following Caffery’s death, Rachel gave birth to three more children, William, Andrew, and Mary, expanding the Atlas brood from five to eight. Three long years elapsed before their permanent residence was solidified. Would they be sold together? Would they be sold apart or in small groups? If they were broken apart, would they ever see each other again? We can only ponder why they chose not to abscond after weighing all the prospects before them like escaping into nearby Texas or assuming a new identity as free people of color in neighboring Louisiana. On the other hand, successfully escaping from legalized bondage with seven children under the age of 10 seemed almost impossible. Fate could not be changed, and as a result, the trajectory of American history was forever altered. They instead sowed the seeds of liberty for their descendants to reap, and they’d come to collect their harvest 100 years later during the Civil Rights Movement.

Not Tara, But Still Slavery

John Caffery, Jr. was born about 1798 in Tennessee to a much desired pedigree – his maternal grandfather, John Donelson, established the city of Nashville with his grand uncle, President Andrew Jackson. Caffery and his brothers Donelson and Jefferson explored the option of living in Louisiana following John’s military service during the War of 1812 and eventually settled in St. Mary Parish in southern Louisiana. Other family members also left Tennessee and moved to the Delta where they settled in Claiborne and Warren Counties in Mississippi.

By the time of his death, Caffery was in exile in Arkansas. In the decade that preceded, he was embroiled in a dispute with his sister in law over the estate of his brother Jefferson. That dispute led him to relocate 332 miles from St. Mary to Lafayette County in southwestern Arkansas. How he became the slaveholder of King Sr. and family is still being researched, but based upon an agreement dated June 14, 1850 in Carroll Parish, Louisiana, Caffery was their slaveholder at the time of his death.

Once the estate was settled, King Sr., Rachel, Henry, John, King Jr., William, Andrew and Mary’s lives were divided into shares between Caffery’s descendants – a portion to his niece Rebecca Green and her children and a portion to another niece, Emma Caffery Thomson. The agreement noted that Caffery’s sister, Nancy Caffery Jenkins, his nephew, Donelson Caffery “D.C.” Jenkins, and his nephew-in-law, Hugh Short, purchased the family members’ interests in different proportions and became the new slaveholders of King Sr. and family. The new slaveholders were residents of Carroll Parish in northeastern Louisiana and their new enslaved property had a value of $2,000 in 1850. This is equivalent to nearly $60,000 today.

Hugh Short: Challenging the Traditional Slaveholder Narrative

Popular culture has long played out the war between the states from reenactments to movies to even political speeches. Nearly every angle has been covered in the more than 150 years since the first shots were fired. One aspect that still remains a highly contentious topic is the importance of and implications of chattel slavery in the Civil War. Although the 13th Amendment transformed its existence in 1865, the after effects of the institution still reverberate within America whether it’s in online discussions or when the origins of familiar places or institutions are discovered. The two sides have been at odds for decades, pushing and pulling at each other – a glass half full on one side and one completely empty on the other – and the debates almost always descend into the morality, motivations, intentions of the slaveholding class.

One side argues that attributing anything positive to former masters and mistresses is out of the question based on the face that they had the gall to claim ownership over another human being. In contrast, the other side will debate that the system could not have survived if the worst was always enacted against the enslaved by the slaveholding class. Historical nuance has never been a comfortable concept for Americans to own. In this vein, Hugh Short’s morality, motivations, and intentions challenge even the most ardent person on either side of the slavery debate.

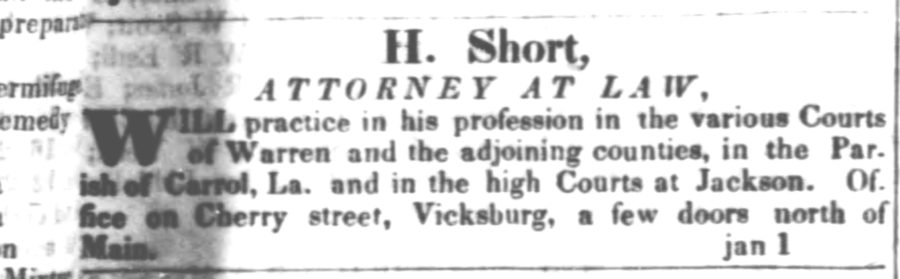

Hugh Short became the sole slaveholder of King Sr. and family following the death of Short’s mother-in-law Nancy Caffery Jenkins in 1858. He was a lawyer by trade but did not shy away from the peculiar institution; he was slaveholder of four other enslaved people by the time he became slaveholder to the Atlas family.

Short was born about 1814 in Pennsylvania. An 1832 graduate of Hanover College in Hanover, Indiana, he was classmates with John Jenkins, Jr. and became his brother law after his September 20, 1835 nuptials to Nancy Rachel Jenkins in Claiborne County, Mississippi.

Stints as the district attorney for Warren County, Mississippi along with several leadership roles within the Democratic Party of the same were followed by a relocation across the river to Carroll Parish, Louisiana in 1847. This was shortly after his uncle-in-law, John Caffery, Jr. died. Short soon amassed several landholdings within the parish including one he called Bellfont Plantation, which is now the Economy Inn located at 9634 US-65, Lake Providence, LA 71254.

Short was known as a great orator and often gave speeches with contemporaries like Jefferson Davis, who would become president of the Confederate States of America. One of his more well known speeches, given on June 8, 1844, called out the Native American Party (also known as the Know Nothing Party) regarding their xenophobic platform, and and made it seem as if he simultaneously called into question the current immigration debate of the 21st century, long ago in the 19th century.

“Mr. Short spoke of the miscalled Native American party as the organization of the whigs to proscribe foreign born citizens whose only crime consists in voting the Democratic Ticket when they become naturalized; he also showed what is true and native policy, the policy of Jefferson – namely receiving the the exile as a brother. He alluded to the constitution and to the rights and guarntees of civil and religious freedom – spoke of the early settlers of this country fleeing from persecution and of the injustice of their descendants inflicting on exiles now, the same evils which their fathers left their native homes & crossed the stormy ocean to avoid.” Vicksburg Weekly Sentinel (Vicksburg, Mississippi), Tuesday, June 11, 1844, page 3. Source: Newspapers.com

Yet, however honorable, thoughtful, and wise his words were, Short was truly arguing against himself. He suffered from his own form of xenophobia that defended the rights of voluntary immigrants yet denied the humanity of those who were forcibly migrated, and however hypocritical it appeared, his attitude was reinforced by the law he practiced.

Perhaps he was never conflicted about what he believed in and was able to separate human emotion from business. One such example was the terms of payment that secured his role as sole slaveholder of King Sr., Rachel, Henry, John, King Jr., William, Andrew, and Mary. The terms served two purposes: they conferred ownership of human beings, while the other created generational upward mobility for his family through payment for the law education of his nephew Donelson Jenkins and the education of his niece Octavia McCarroll. Money he made in his primary profession could have financed this; he was not a large scale slaveholder. On the other hand, he still generated profit from the use of free labor, no matter how small the amount.

Short remained sole slaveholder until his untimely death on August 19, 1862. The country was in the throes of Civil War and some accounts relay that he argued himself to death due to his opposition to southern secession. His will, dated September 29, 1861, adds more fuel to the fire of his contradictory life.

Tracing slaveholders, a document at a time

Pop culture leads many to believe that tracing a slaveholder is impossible to do on paper. This is simply not the case. In haste, many use the slave schedules the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules as a form of verification despite the fact that they largely lack the names of the enslaved. The key to researching the enslaved lies in locating their names – and former slaveholders – in publicly and privately available documents.

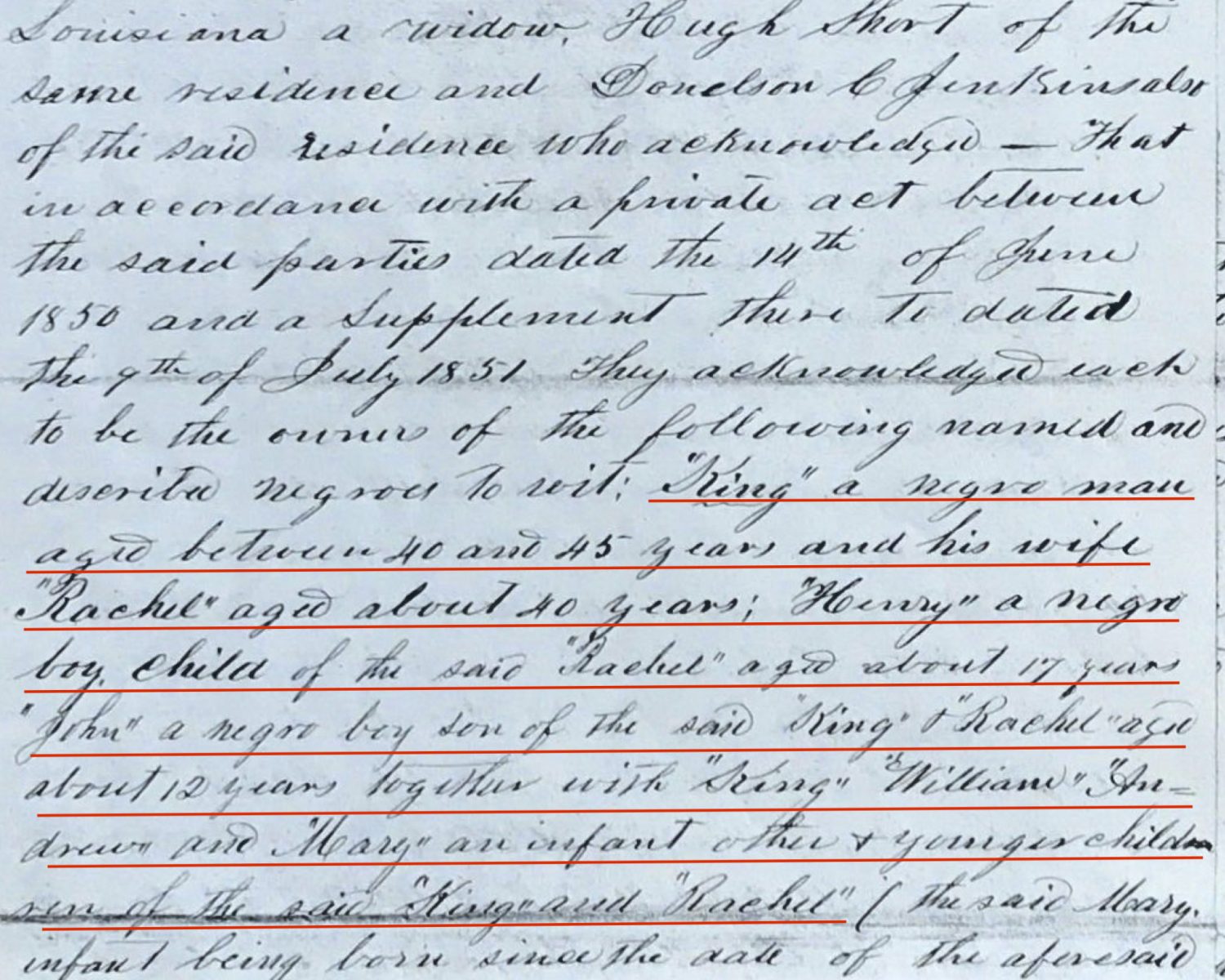

Agreement, 1850

“King, a negro man aged between 40 and 45 years and his wife Rachel aged about 40 years; Henry, a negro boy child of the said Rachel aged about 17 years, John, a negro boy son of the said King and Rachel aged about 12 years together with King, William, Andrew, and Mary, an infant, other and younger children of the said King and Rachel.”

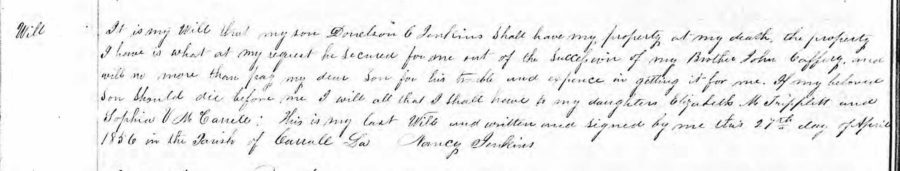

Will, 1856

“It is my will that my son Donelson C. Jenkins shall have my property at my death. The property I have is what at my request he secured for me out of the succession of my brother John Caffery, and will no more than pay my dear son for his trouble and expense in getting it for me.” The property referenced by Nancy Caffery Jenkins was King Atlas, Sr., his wife Rachel Day, and their children.

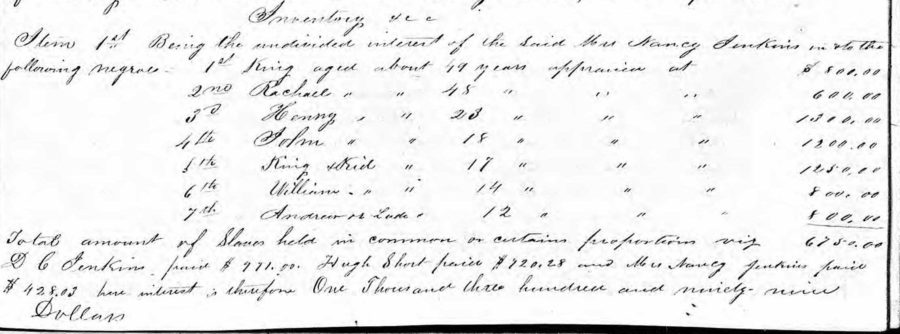

Inventory, 1858

“Item 1st being the undivided interest of the said Mrs. Nancy Jenkins in the following negroes – 1st King, aged about 49 years appraised at $800, 2nd Rachel, aged about 45 years appraised at $600, 3rd Henry, aged about 23 years appraised at $1,300, 4th John, aged about 18 years appraised at $1, 200, 5th King + Kid, aged about 17 years appraised at $1,250, 6th William aged about 14 years appraised at $800, 7th Andrew or Luke aged about 12 years appraised at $800.”

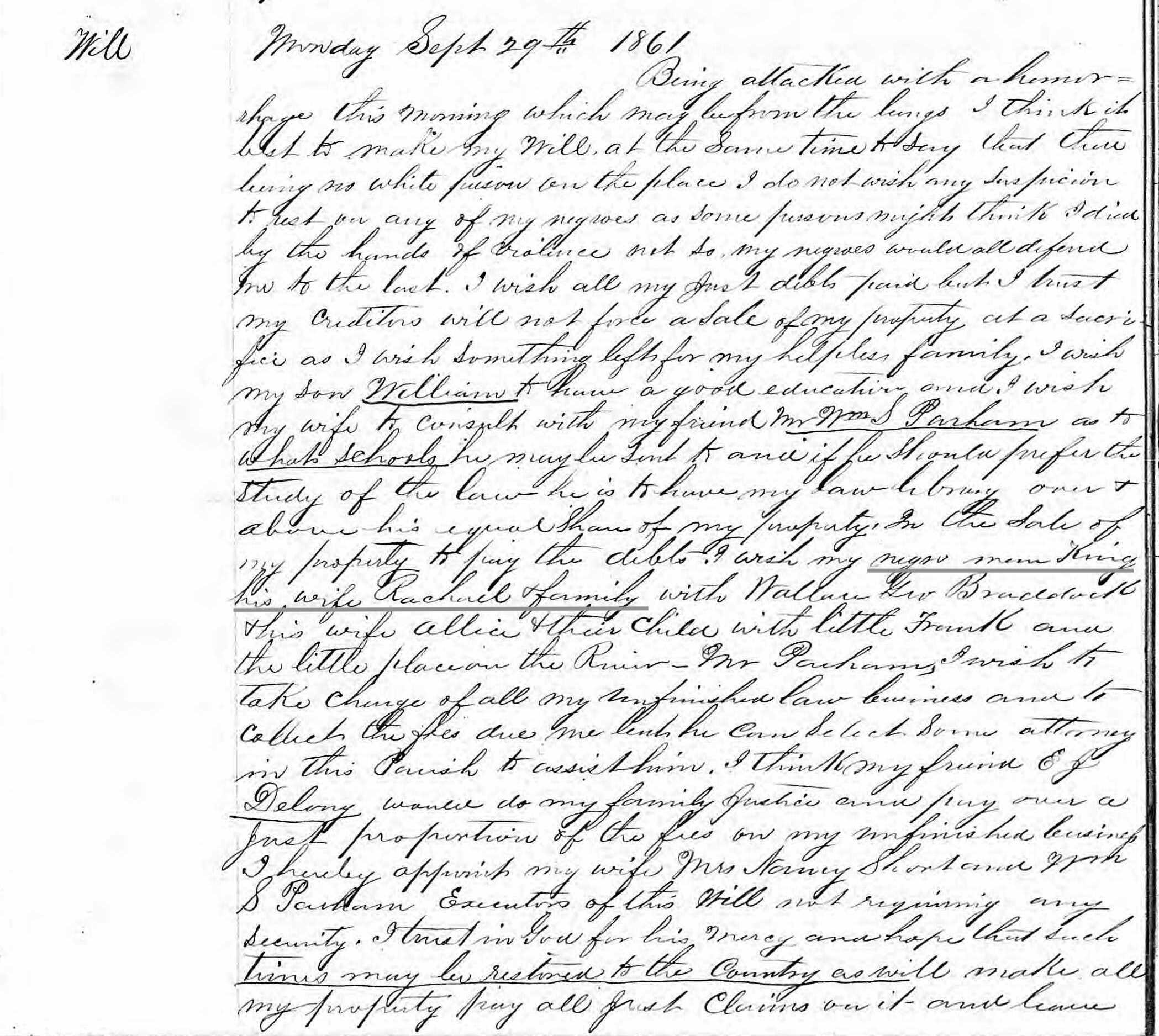

“Monday, September 29, 1861

Being attacked with a hemorrhage this morning which may be from the lungs, I think it best to make my will at the same time today. That there being no white person on the place, I do not wish any suspicion to rest on any of my negroes as some persons might think I died by the hands of violence – not so – my negroes would defend me to the last. I wish all of my just debts paid but I trust my creditors will not force a sale of any property at a sacrifice as I wish something left for my helpless family. I wish my son William to have a good education and I wish my wife to consult with my friend Mr. Wm S Parham as to what schools he may be sent and if he should prefer the study of the law, he is to have my law library over and above his equal share of my property. In the sale of my property to pay the debts, I wish my negro man King, his wife Rachel and family, with Wallace, Geo Braddock and his wife Allice and their child with Little Frank and the little place on the river [Bellfont Plantation]. Mr. Parham, I wish to take charge of all my unfinished law business and to collect the fees due me that he can select some attorney in this parish to assist him. I think my friend E.J. Delony would do my family justice and pay over and just proportion of the fees on my unfinished business. I hereby appoint my wife Mrs Nancy Short and Wm S Parham executors. I trust in God for his mercy and hope and hope that such times may be resolved to the country as will make all my property pay all just claims on it and have a support for my family. If it be so ordered that I shall not see you anymore on earth, my dear family farewell. H. Short”

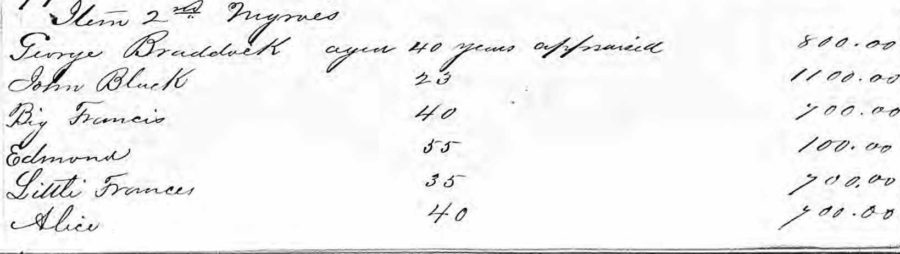

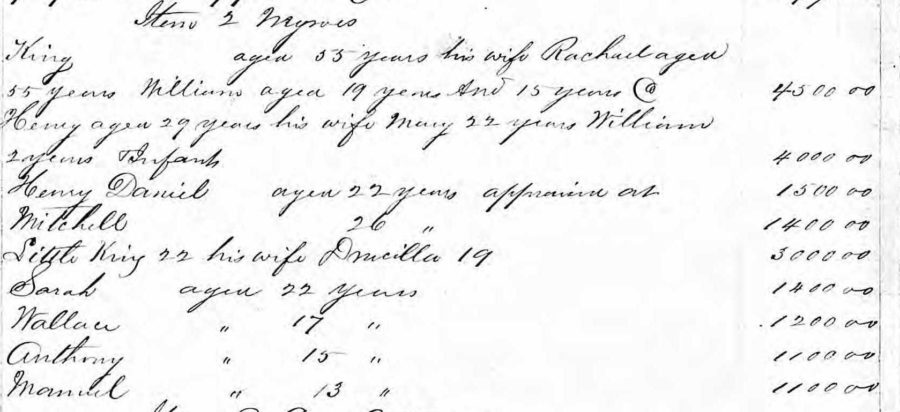

Inventory, 1862

Top: “John Black, age 23 years, appraised $1,100,” who was John Atlas, son of King Atlas, Sr. and Rachel Day. This small list of enslaved is believed to have lived at Short’s property in the town of Lake Providence.

Bottom: Second list of enslaved people living at Bellfont Plantation, just south of Lake Providence, East Carroll, Louisiana. “King, age 53, his wife Rachael, aged 55 years, William aged 19 years, And (Andrew), age 15 years appraised at $4,500;” “Henry, aged 29 years, his wife Mary, 22 years, William, 2 years, and infant, appraised at $4,000;” “Little King, aged 22, his wife Druscilla, aged 19, appraised at $3,000.”

Why was the welfare and perception of Short’s enslaved a concern upon his death? The wills of most slaveholders are clear in their primary intention that their heirs benefit from the enslaved they bequeathed to them financially. Significantly fewer considered the enslaved worthy enough to emancipate them. Short toed the line between those extremes in a unique way that is hard to reconcile, especially in light of how perceptions have shifted over time. Was Short benevolent to his enslaved and if so, did said benevolence truly matter if he never thought them valuable enough in personhood to free them? Did the Atlas family respect and honor Short beyond their relationship to him as enslaver or was such respect and honor mandatory as a condition of their status in society? The answers to those questions appear lost to time.

King Sr., Rachel, Henry, John, King Jr., William, Andrew, and Mary were one of Short’s most valuable possessions. Their financial value noted in Short’s estate was upwards of $12,000, which is more than $320,000 today. By 1870, the Atlas family would emerge from enslavement with a combined personal estate value of $2,200, which is $43,000 today, an almost unheard of sum at the time. Exactly how King Sr. and his family achieved such financial status is unknown. Short could have given them permission to be hired out to others and keep the proceeds from their work while they were enslaved, which was legal based on the civil code in the state of Louisiana at the time. Their niche work as house servants, blacksmiths, agrarians, and even a veterinarian clearly made them sought after in the community.

In the end, there was no amount of money that can compare to the foundation they laid and the legacy they entrust to more than 3,800 descendants. Theirs is a story that began in a world that supported a system where humanity was pushed down enough to let greed rise, yet in the minds of those who provided the fuel to keep it going, that system had long ago been burned to ashes.

King Atlas, Sr., born between 1807-1810 in Kentucky and his wife, Rachel Day, born between 1807 and 1820 in Virginia, are the great great great grandparents of Nicka Smith. To date, nearly 70 of their descendants have participated in autosomal DNA testing. For more information on them and their family, visit AtlasFamily.Org