This post is part of the Trask 250 series which documents the lives of more than 250 formerly enslaved of the Trask and Ventress families of Louisiana and Mississippi.

James Alexander Ventress wanted his power back. An insurmountable weight was on the plantation empire he had acquired through his own means and through inheritances he had access to through his marriage to Charlotte Davis Pynchon Ventress. Being stripped of citizenship following the Civil War meant his legal rights to the following had vanished:

Freedom to express himself.

Freedom to worship as he wished.

Right to a prompt, fair trial by jury.

Right to vote in elections for public officials.

Right to apply for federal employment requiring U.S. citizenship.

Right to run for elected office.

Freedom to pursue “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Ventress was use to enjoying these rights as he had been a legislator in the state of Mississippi before the war. He was active in his community, created the legislation that established the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) and appeared to support the union for which he served. On the other hand, as evidenced by a letter printed in The Oxford Intelligencer (Oxford, MS) on February 27, 1861, Ventress was an ardent supporter of the system of enslavement and the right of him, and his fellow Americans, to participate in it, no matter its morality or who it disenfranchised.

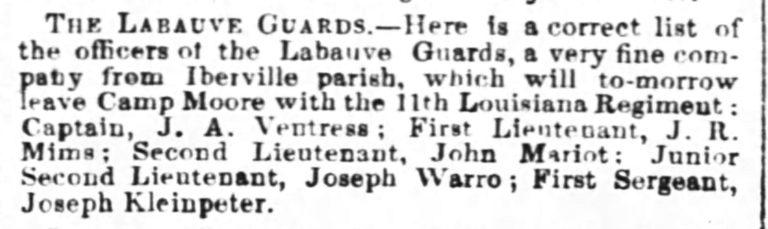

By August 1861, Ventress’ tenor ascended to contralto status. He volunteered for service and was a first lieutenant of the Labauve Guards out of Iberville Parish, Louisiana who would soon be part of company B of the 11th Regiment of the Louisiana Infantry.

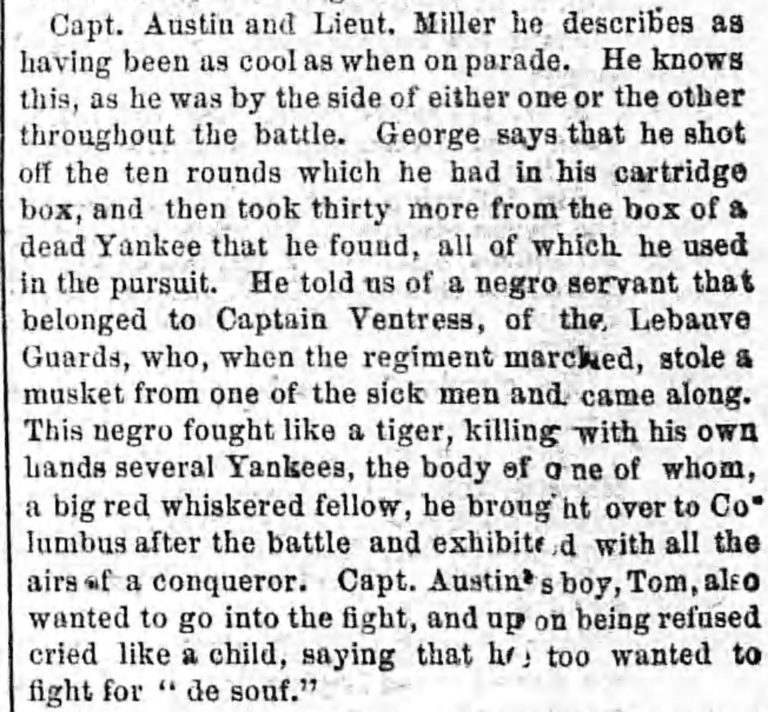

Even tales of confederate support and battlefield fighting from an unnamed man enslaved by Ventress were recounted by that November.

Yet, there was no amount of prose, open letters, or alleged “happy to stay beneath your foot and fight for it” by an enslaved man that could fix the fact that Ventress’ status had been drastically diminished after the war between the states. Desperate times called for desperate measures and he was not above reaching out as far as the president of the United States to make sure that weight was removed.

In May 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued what is known as the amnesty proclamation, a declaration which restored citizenship rights to a 14 specific classes of confederates. Ventress didn’t qualify for reinstatement since his wealth before the war exceeded $20,000 (equivalent to $554,253.18 today) and he held positions within the confederate military. His only option was to petition directly to the president, despite the fact that it completely contradicted what his words and actions were a few years earlier.

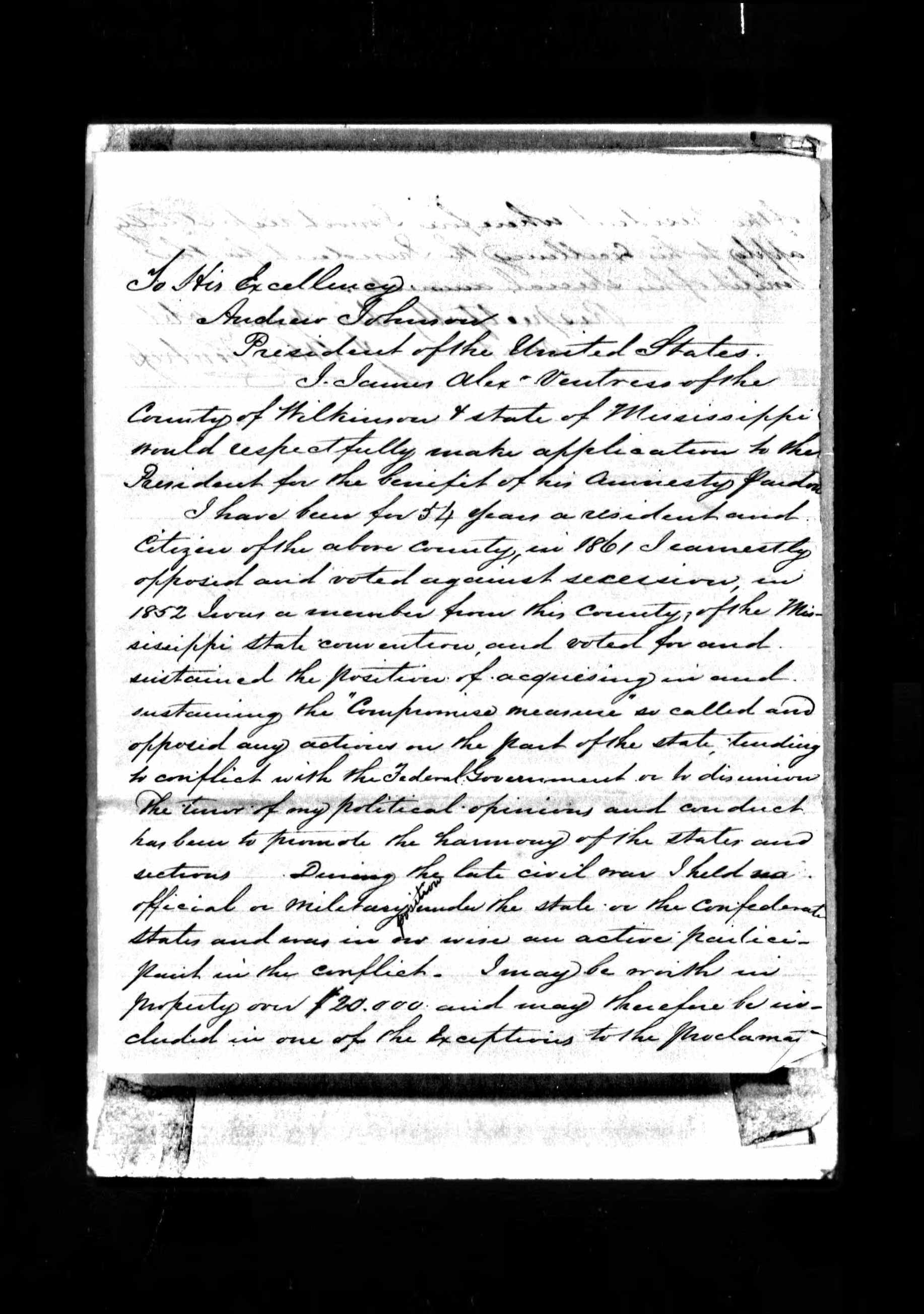

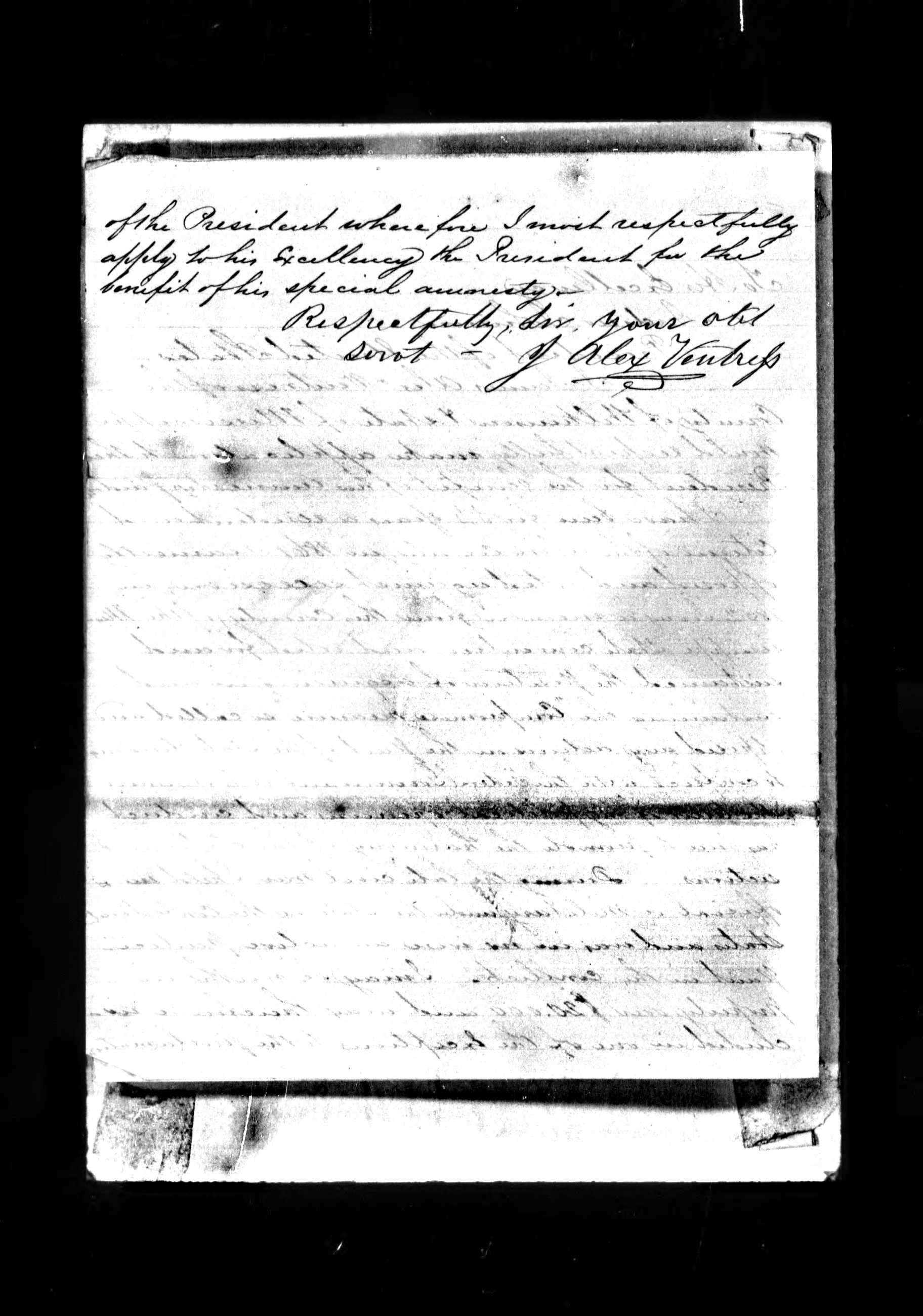

“To His Excellency

Andrew Johnson

President of the United States

I, James Alex[ander] Ventress of the county of Wilkinson and the state of Mississippi would respectfully make application to the President for the benefit of his amnesty pardon.

I have been for 54 years a resident and citizen of the above county. In 1861, I earnestly opposed and voted against secession. In 1852, I was a member from this county of the Mississippi State Convention and voted for and sustained the position of acquiescing in and sustaining the “compromise measure” so called and opposed any actions on the part of the state pleading to conflict with the Federal Government or to disunion. The tenor of my political opinions and conduct has been to promote the harmony of the states and sections. During the late civil war I held official or military positions under the state or the confederate states and was in and was an active participant in the conflict. I may be worth in property over $20,000 and may therefore be included in one of the exceptions to the proclamation of the President wherefore I must respectfully apply to his excellency the President for the benefit of his special amnesty.

Respectfully sir your obi[dient] servant,

J. Alex Ventress”

Ventress, Jas A. Surname Range: Sl-Yo. Ancestry.com. Confederate Applications for Presidential Pardons, 1865-1867 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008. Original data: Case Files of Applications From Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons (“Amnesty Papers”) 1865-1867; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1003, 73 rolls); Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917, Record Group 94; National Archives, Washington, D.C. Accessed 4 Feb 2019.

Perhaps Ventress had a change of heart. It’s unclear as to whether his motivation to about face was purely based on financial and/or negative social ramifications. He definitely had a lot to lose.

Help came quickly. Just two months after the amnesty proclamation, Ventress was given the oath to restore his citizenship rights.

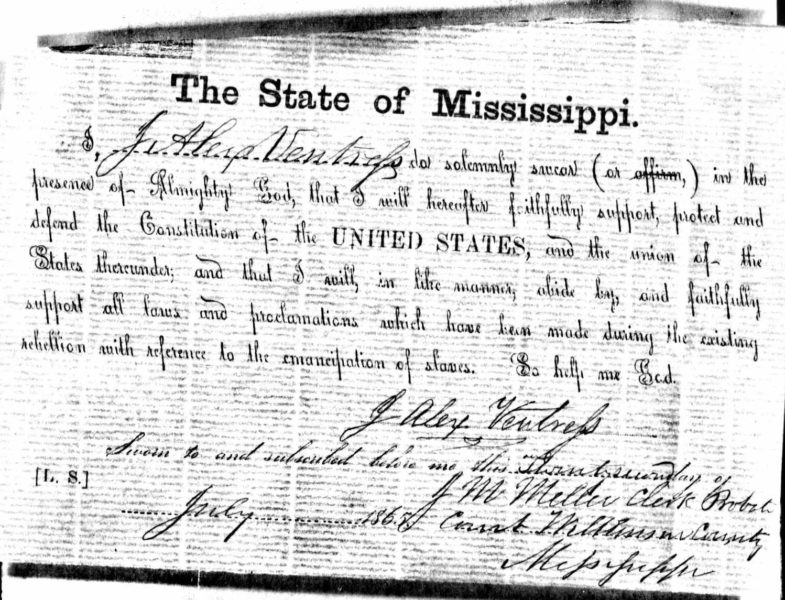

“I, J. Alex Ventress, do solemnly swear or affirm, in presence of Almighty God, that I will henceforth faithfully support and defend the Constitution of the United States and the Union of the States thereunder. And that I will, in like manner, abide by and faithfully support all laws and proclamations which have been made during the existing rebellion with reference to the emancipation of slaves, so help me God.

Sworn and subscribed to me this this twenty-second day of July, 1865; J. M. Miller, Clerk, Probate Court, Wilkinson County, Mississippi.”

Ventress, Jas A. Surname Range: Sl-Yo. Ancestry.com. Confederate Applications for Presidential Pardons, 1865-1867 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008. Original data: Case Files of Applications From Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons (“Amnesty Papers”) 1865-1867; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1003, 73 rolls); Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917, Record Group 94; National Archives, Washington, D.C. Accessed 4 Feb 2019.

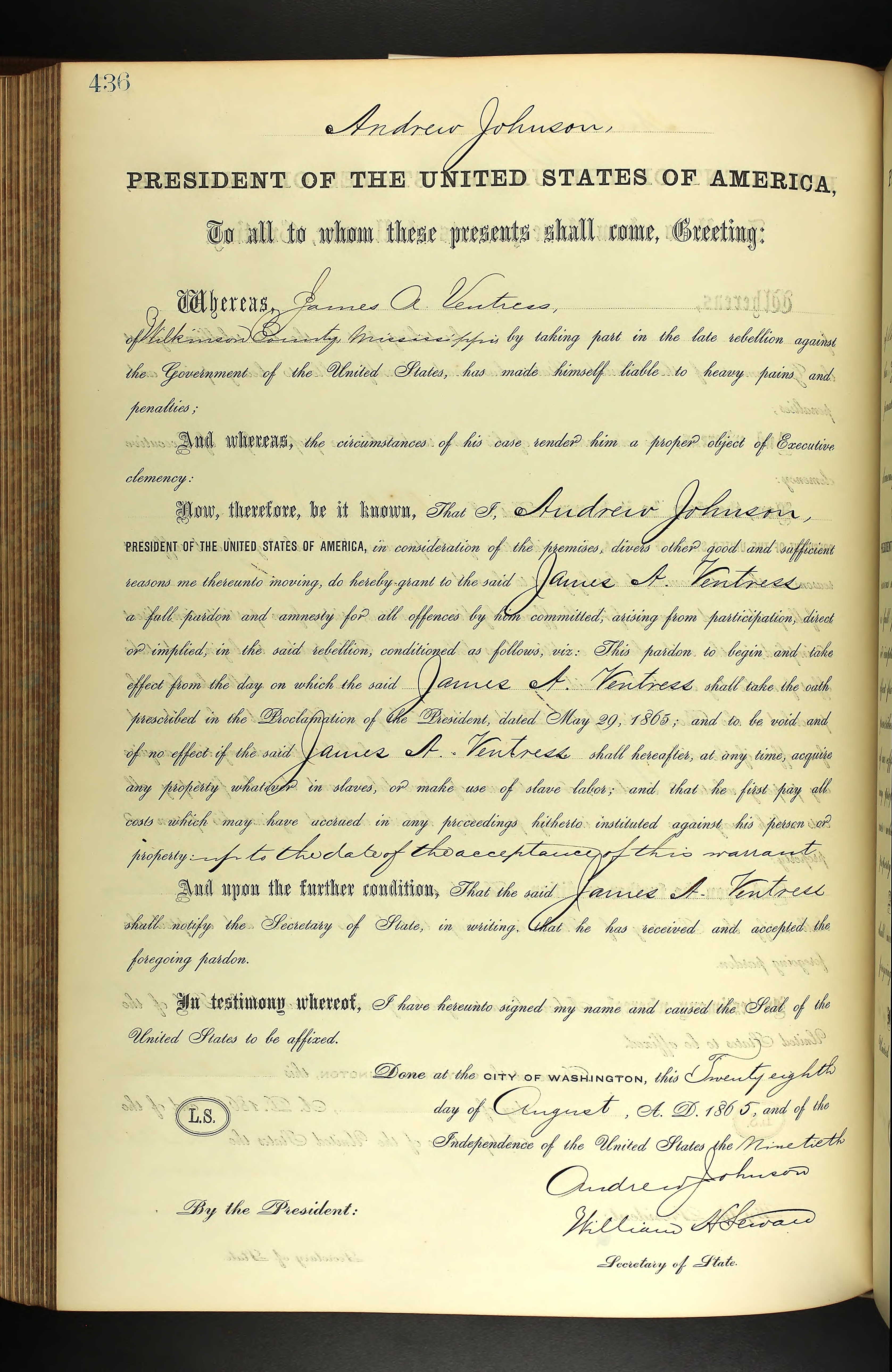

An official pardon was issued on August 28, 1865 and was signed by President Andrew Johnson and William H. Seward, secretary of state. Ventress would only enjoy his rights to citizenship for two years before his death in 1867.

Postscript

At first glance, Confederate Applications for Presidential Pardons (Ancestry, Fold3) and Pardons Under Amnesty Proclamations (Ancestry) may seem of little value to a researcher who is documenting the formerly enslaved. Upon deeper review, these two record sets can provide much needed context on the motivations of former slaveholders which can shed more light on the stories of their formerly enslaved as they emerged as free people during Reconstruction. Learn more about that time period in episode 76 of BlackProGen LIVE, “Reconstruction and the Aftermath Named Jim Crow.”