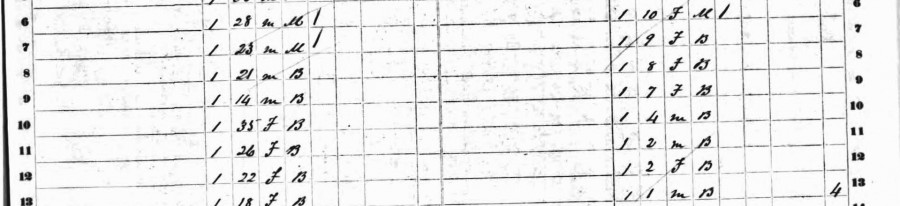

Assuming a line on the slave schedules is an ancestor without supporting documentation or that the nearest white person is a former slaveholder bastardizes all the family historians and genealogists who have spent decades conducting African American genealogy. (Featured Image: 1860 US Slave Schedules, Goingsnake District, Cherokee Nation)(2)

I waited a little while until I had THE topic for season 3 of Finding Your Roots to blog about. Nothing was grabbing me. Until episode 3. Last season, we had the epic issues with the topic of slavery and Ben Affleck and the Green Jeter fiasco. Then, lawd, lawd, lawd. LOL

Episode 3 featured comedians Maya Rudolph and Keenan Ivory Wayans along with writer/producer Shonda Rhimes. An awesome set of folks to document, right? All was going well in this episode. We had some photos, some stories, some new discoveries and then…and then…

We had a blank line.

With an age.

With a sex.

With a race.

And the guests were told that “this was their ancestor.”

And a couple of them cried.

Now, even if you don’t do African ancestored genealogy, this sounds fishy, right? I mean, how does someone know that a blank line with just an age, sex, and race is their ancestor? Believe it or not, this is a tactic that has been used MANY times over the years.

A Hurdle, Not a Brick Wall

Researchers near and far have tried their hardest to get their African American ancestry traced back to the 1870 U.S. Census – the first federal census that was conducted following the 13th Amendment or the end of slavery as it was known. This census is often looked at as having the most clues for being able to determine if ancestors were former slaves who were emancipated by the 13th Amendment, former slaves who were emancipated before the 13th Amendment, and/or ancestors who were born into or during slavery.

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution declared that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Formally abolishing slavery in the United States, the 13th Amendment was passed by the Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the states on December 6, 1865. (1)

Pulling Out the Wizardly, Signs, Wonders, and the Big Chief

Once a researcher finds their ancestor on the 1870 U.S. Census, the next goal they usually have is to track down possible slaveholders for their ancestors.

One of the ways I’ve seen MANY people attempt to do this is by searching for the “nearest white person” who carries the same surname as your African American ancestor and lives in the same county or region. Some have also looked at “the nearest white person” without the same surname who lives close by an African American ancestor (on the same page, a page before, after, etc.) who may have a sizable amount of personal or real estate (which is captured on the 1870 US census) and may have had that estate before the 13th Amendment or 1865.

Then, using this logic, a researcher may choose to search the 1850 and 1860 United States Slave Schedules for the identified “nearest white person” and hone in on one of their formerly enslaved who is around the same age, is the same sex, and race of the later emancipated African American ancestor. But you see I didn’t mention that any other evidence was used to verify that this was in fact the case, right?

No bill of sale.

No estate inventory.

No oral history.

No probate record.

No will.

No account books.

No insurance paperwork.

No Dawes Application Packet or Card.

Nothing other than a hunch, the same surname and/or being neighbors, and a blank line. That’s it. I should hit the jackpot based on what was shown on Finding Your Roots, right?

I know the names many of my formerly enslaved ancestors. This goes back to my great great grandparents, or my grandparents grandparents. The table below shows just how jacked up this reasoning is and how you’d need to perform an intervention if I tried researching all these dead leads. Keep in mind that slave children took on the disposition of their mothers – so their mother’s owner was their owner.

| Name | Birth Date and Location | 1870 US Census Location | “Nearest White Person” on the 1870 Census or 1850 or 1860 Slave Schedules | Confirmed? |

| King Atlas, Jr. | Between 1840-1845 in Arkansas, USA | Carroll Parish, Louisiana, USA | There aren’t any. For the 2 pages that make up “Balfour Plantation,” not a single person of European descent lives there. No European Atlas’ in the parish – although some Atteles south Louisiana who I have never found owning slaves. | Nope. Beat this horse, dead, deader, and deaddeader. Mother was allegedly a Dugan, but no “nearest white person” on the slave schedules nearby with that name.

Update: Confirmed the former slaveholders were Hugh Short and John Caffery of Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas. Neither were living in 1870 or have the surname of Atlas. |

| Alice Smith | Between 1850-1853 in Alabama, USA | Not located. Relation and name based on 1880 US Census, oral history, and vital records. | Not located. | Nope. Mother’s maiden name unknown as today. |

| John Lee | Likely between 1850-1860 in southeast Arkansas (Desha, Chicot, Drew, or Ashley Counties based on DNA matches) | Not located. Name and relation based on labor contracts, oral history, and vital records. DNA confirmed to be bi-racial and may have been a free person of color. |

|

Nope. Not more than a potential blank line to go on; mother’s maiden name unknown as today.

Update: Confirmed the former slaveholder were Williamson Liles and James Kerr of Kentucky and Louisiana. Kerr was enumerated on the same census page as John Lee in 1870, but was not the nearest white person and does not share the same surname. |

| Clora Evans | Between 1850-1860 in Carroll Parish, Louisiana, USA | Carroll Parish, Louisiana, USA | Neither J.H. Frellsen nor W.H. Wood were her slaveholder.

Confirmed: Lucinda Bullock (nee Brashears, Bush, Jacobs, Grace), William D. Bush (U.S. Civil War Pension file of uncle, oral history, estate inventories, deeds) |

|

| Robert Taylor

OR Thomas Jefferson Chisum |

Between 1850-1858 in Virginia, USA

or January 3, 1852 in Texas, USA |

Not located. Relation and name based on 1880 US Census and oral history.

or |

Not located. 1860 Slave Schedules note A LOT of Taylors in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana and Natchez, Adams County, Mississippi, USA, but is that enough?

or Was never enslaved. |

Nope for both. |

| Amanda Jackson | About 1850 in Mississippi, USA | Not located. Relation and name based on 1880 US Census. | Not located. | Nope. Mother’s maiden name unknown as today. |

| George Barber | Born about 1834 in Virginia, USA | Catahoula Parish, Louisiana, USA |

|

Nope. Mother’s maiden name unknown as today. |

| Susie Unknown | Born about 1840 between in Kentucky, USA | Catahoula Parish, Louisiana, USA | Same as George. Since her maiden name is unknown, Tilman Gilbert above could be her slaveholder since they were born in the same state, but is that enough? | Nope. |

| Benjamin James Sewell | Born about 1859 in Louisiana, USA | Not located. Relation and name based on 1880 US Census and vital records. | Benjamin Sewell on 1860 Slave Schedules in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, USA. | Nothing to go on other than a surname and proximity. |

| Easter Parker | Born between 1857-1864 in Mississippi, USA | Not located. Relation and name based on 1880 US Census, oral history and vital records. | No one with similar sounding surname for her mother, Fountain, found on the 1860 Slave Schedules in the area. | Nope.

Update: Confirmed former slaveholders are the Trask and Ventress families of Massachusetts, Louisiana, and Mississippi. None were living near her or her family in 1870 and their surnames were not taken by family members. |

| John Holmes | Unknown. | Not located. Name based vital records. | Should I throw something at the wall to see if it sticks? | Nope. |

| Eliza Unknown | Unknown. | Not located. Relation and Name based vital records. | See notation for John. Also, no maiden name yet. | Nope. |

| Isaac Rogers | About 1850 in the Cherokee Nation (now northeast Oklahoma) | Miami, Osawatomie, Kansas, USA |

|

None of these people were his slaveholder.

Confirmed: Alzira May Price (Based on mother and childrens Dawes App Packets and Cards) Slaveholder’s slave schedules included in Arkansas. |

| Sarah Vann | About 1860 in the Cherokee Nation (now northeast Oklahoma) | 1865 Kansas State Census – Miami, Osawatomie, Kansas, USA |

|

None of these people were her slaveholder.

Confirmed: Rider Fields (Based on brother’s Dawes App Packet and Card, Eastern Cherokee Application) Slaveholder’s slave schedules included in Arkansas. |

| John Walter Allen | Unknown. | Not located. Relation based on Dawes Application Packet and Card, oral history, and vital records. | N/A | Not enslaved based on Dawes App Packet and Card of daughter. |

| Sarah Bean | Between 1850-1858 in the United States | Not located. Relation based on 1880 US Census and Dawes Application Packet and Card. | 1860 Slave Schedules – Mark Bean, Ruth Bean, Leonidas Bean, E. Bean…all living in Arkansas, not the Cherokee Nation | None of these people were her slaveholder.

Confirmed: Mary Pauline Starr Rider (Dawes App Packet and Card) Slaveholder’s slave schedules included in Arkansas. |

So, out of 16 people, I could use this “nearest white person” theory on one, possibly two if I’m being generous.

The point being, unless you’ve got supporting information or documentation, there is no way to confirm a slaveholder using this theory or with a blank line on a slave schedules. It makes it look like the field of African American genealogy is neither needed nor based in solid scholarship when we make hasty conclusions.

Please, let’s stop prostituting the slave schedules for our own agendas.

Sources

(1) “13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” Primary Documents in American History – Web Guides. The Library of Congress, 30 Nov. 2015. Web. 19 Jan. 2016. <https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/13thamendment.html>.

(2) Township : Going snake district, page 21. Ancestry.com. 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. M653, 1,438 rolls. Accessed January 19, 2016.

On the recent episode with artist Kara Walker, they did it again! The program finds ancestor David Walker in the 1880 census of Coweta County, Georgia. The family tree prepared for the show states he was born in Georgia (which matches what the 1880 census shows). The narrator states that because he was born in 1833 he spent the first 30 years of his life in slavery (how did they rule out the possibility, however slim, of him being FPOC? And where was he in 1870?). Something was edited out of the program because the next statement is, “We next looked for a master in South Carolina with the surname Walker. We soon found a slave schedule for a white man named Samuel Walker” who listed a slave the right age to be David Walker. Even though the narrator admits they had no name evidence, Dr. Gates announces to Kara, “You are looking at the listing for your great-great-grandfather David Walker.” Cue the weeping. How did that happen? Surely not so simple? So many unanswered questions!

Thank you Nicka, this is very good research!

Vickie M. Bass

Totally Awesome

I did research on my Parental family from 1845 to present. He was borned in Mississippi and move to Louisiana after the 13 amendment. I could not connect the dots. From Mississippi to Louisiana. Who was his father?

I’ve only been researching my family for two years. But in the beginning I had no faith in the age, sex and surname on slave schedules for finding an ancestor. Having spent years using deductive reasoning a systems trouble shooter, just common since told me that it would be foolish to make an assumption based with no documentation. My paternal grandfather, born in 1888, who’s family, as far as we know, has it’s origins in Lauren’s Cty., S. Carolina. He knew his paternal grandfather, Joel/Joseph or Joshua Ligon, born 1828, supposedly in S. Carolina, per 1880 and 1900 census. According to my grandfather, Joel was never a slave. There for he must have been born a FPOC. His first for children where born in the 1850’s per census records, one was my grandfather. I have found no birth records on either generation in S. Carolina which is not unusual. Off chance that gramps was incorrect in stating that ggrandpa wasn’t a slave, I checked the 1840,50 and 60 slave censuses for the two white Ligon families in the area. No male slave of the appropriate age for Joel. Since I’be never heard of another location of the family living anywhere else, I’m standing in front of a brick wall. Assuming Joel was actually a FPOC, I reviewed Margaret Peck ham Motes indexing of the 1850 US Census for FPOC in S. Carolina on the chance that maybe Joel relocated to Lauren’s Cty. right after the census was taken. Studying census, including the 1850 and other records for FPOC in Virginia and N. Carolina with the same Ligon surname, I discovered several families had been around since the mid to late 1700’s. But, to my surprise the Motes index for S. Carolina listed not one Ligon person or family surname. I’ve seen others with the same reactions on other of Dr Gates genealogy programs and just shook my head. It makes for great suspense and dramatic finality.

Glad to see I wasn’t the only one who picked up on that “slight of hand methodology” during the episode.

Pingback: January 2016 Reading Recap – Life in the Past Lane

By a strange coincidence, we’ve actually been able to identify a shared white slaveholder ancestor through DNA testing. (We are three white cousins and two black women.) The three white women are two cousins and one second cousin, and we know our common ancestry (even though we only discovered each other through the testing). Because of that, we’re fairly certain the two black women (and others, in fact) to whom we are related are connected to the same family. We can even pinpoint the latest possible connection, because he moved out of the slave-holding area. But from all our research, we can’t put the white family and the black family even in adjacent states! Any ideas?

Hi Jacqueline! Thanks for commenting. My suggestion in your case is to trace the slaveholding families locations first. Their property went where they went, and this is especially the case with slaves who were working in their homes. If they went on vacation, so did their personal slaves which means that the liaison that created the relation could have happened outside of the south. Search for diaries, letters, or accounts of the slaveholding families and their F.A.N. Club (friends, associates, and neighbors). They may hold clues as to when and where they traveled and would likely mention that their slaves were there as well. Happy hunting and keep me posted on what happens.