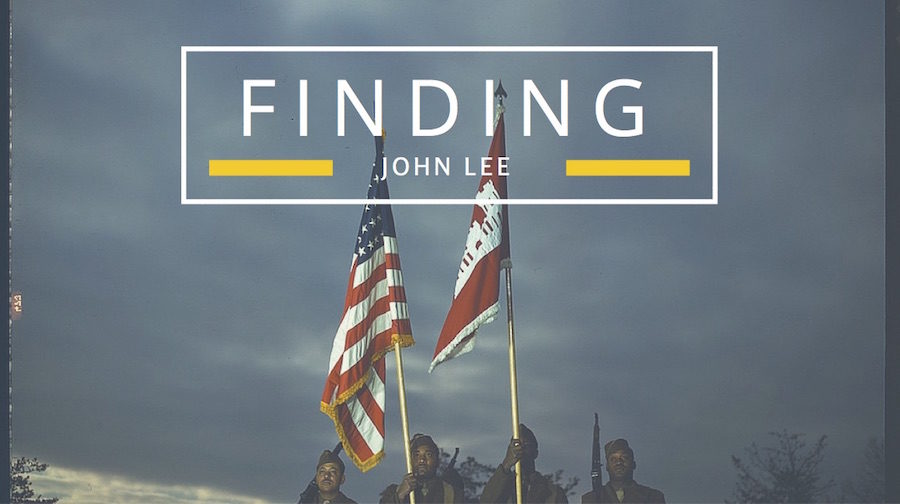

The story of a fugitive slave turned Civil War veteran whose bravery helped me break through a more than 100 year old genealogical brick wall.

There was nothing that could have prepared me for the reality that sat in front of me. It was legal sized, blue in color. Thick in width, chalk full of handwritten notations that can take years analyze. It looked intimidating, but I was ready for the challenge. I had waited a lifetime for the information that stack of papers had and my gut was telling me that the answers me and Cousin B. longed for were sitting right there on my table.

“Before he and his brother Lemas ran away…”

At this point, I was pretty certain that Asberry Lee was my great great uncle, the brother of my mysterious Grandpa John. Oral history was there. The DNA was there. I had even found the paper trail. I couldn’t really ask for much more. But then, a story emerged that I couldn’t ignore.

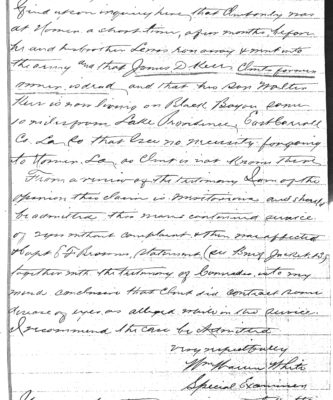

Amongst the affidavits from folks like my great great great grandmother, Jemima Taylor Lee, and Uncle Asberry’s army comrades, lay a summation note of sorts from a man named William Warren White. White was a special examiner for the Bureau of Pensions and that notation, dated February 16, 1890, held an important clue:

“Find upon inquiry here that [claimant] was at Homer a short time, after months, before he and his brother Lemas ran away and went into the army and that James D. Kerr, [claimaint’s] former owner is dead and that his son Walter Kerr is now living on Black Bayou some 10 miles from Lake Providence, East Carroll Co. LA. So that I see no necessity for going to Homer, LA as [claimant] is not known there.” (1) – Wm Warren White, February 16, 1890, Little Rock, AR

Asberry and Grandpa John both were born in Carroll/East Carroll Parish, Louisiana and the notation by White notes that their former slaveholder Kerr had taken them to Claiborne Parish, LA before Asberry ran away back to Carroll/East Carroll to enlist in the United States Colored Troops 47th regiment on May 1, 1863. Let’s dissect this and some other things in the pension file for a second.

Asberry Lee:

- escaped for nearly 125 miles from the plantation he was enslaved on;

- managed to evade being captured by his former slaveholder, slavecatchers, or just some random person;

- enlisted in the Union troops;

- survived the Civil War despite the fact that more than half a million other men died;

- went blind;

- lived long enough and provided enough proof to obtain a pension where it detailed all these events.

Based on Google Maps’ estimation, the dangerous journey would have taken him almost two days by foot.

If Asberry wasn’t as brave as he was, I doubt I would ever have cracked this case.

Signs of the Times

On April 28, 1862, the city of New Orleans was surrendered to Union troops and by May 1, the army began moving en masse to take over the largest city in the Confederacy. (2) News quickly spread throughout the state, and in response, planters were instructed by Confederate Colonel G.T. Beauregard (3) to burn one of their most prized and valuable possessions, cotton.

Kate Stone, a Civil War diarist from Madison Parish, LA (just south of Carroll/East Carroll), detailed the smoky sight.

“[May 22, 1862:]We have found it is hard to burn bales of cotton. They will smoulder for days. So the huge bales are cut open before they are lighted and the old cottons burns slowly. It has to be stirred and turned over but the light cotton from the lint room goes like a flash. We should know, for Mamma has $20,000 worth burning on the gin ridge now; it was set on fire yesterday and is still blazing.” (4)

Stone’s family had burned the equivalent of $480,000 (5) in today’s money at the behest of General Beauregard.

The parish history discusses what the scene was like for slaveholders and their enslaved:

“The presence of Federal troops in Providence prompted many area planters to send their Negroes and cotton to the Macon hills to avoid capture.”

“Many slaves looked upon the Federal troops as liberators, and ran away from their masters into the Federal camps. Tension between master and slave, along with the growing threat of Federal raids on the isolated plantations, forced more planters to desert their homes and flee inland to the Macon hills and beyond. Some residents of Carroll and Madison even ‘refugeed’ to Texas.” (6)

Kerr, Asberry and Grandpa John’s owner, was documented in the 1860 U.S. Census (7) as living in Carroll/East Carroll Parish with $65,000 worth of personal estate and 57 slaves (8). By 1870, he was in Claiborne. Based on the parish history and the account of Kate Stone, it appears as though Kerr had to have left Carroll/East Carroll between 1861-1863. This means that Asberry had to have ran away during this time period too.

Just The Right Time

Asberry didn’t get his pension initially. It took seven years for him to prove that his failing sight, and eventual blindness, was caused by an accident where sand blew into his eyes while on duty near Pineville, LA. But White proved to be the examiner he needed for his case approved. A bit of genealogical serendipity exists for White’s involvement as well.

“June 5, 1890: Personal – Capt. Warren White, Special Examiner, of Washington, and son, Nelson, are ill with malarial fever.” (9)

“June 14, 1890: City News – The remains of Capt. Warren White, the Special Examiner of Pensions, who died Thursday evening from malarial fever, were shipped last evening to Ballston Spa, N.Y. for burial.”(10)

White submitted Asberry’s pension for approval on February 16, 1890. He was dead just three months later.

I’m clear that it took a perfect storm to get me to my findings. It took methods, new methods, and the two things combined to get to my conclusion. While there were times that I wanted to give up, or just accept that I would never get any answers, I’m writing this today to tell you (yes you reading this!), that you shouldn’t give up either. You could gain an amazing legacy yourself. 😉

Sources

(1) US Army Pension, Asberry Lee, widow Isey Lee, USCT 47th Infantry, Company B, invalid pension filed February 20, 1883, application no. 473.097, certificate no. 672.879, filed in LA, widow’s pension filed January 23, 1892, application no: 538.195, certificate 370.279. Claim note from Wm Warren White, special examiner, dated February 16, 1890, Little Rock, AR.

(2) United States. National Park Service. “Battle Summary: New Orleans, LA.” National Parks Service, CWSAC Battle Summaries, American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP). U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web. 27 July 2016. <https://www.nps.gov/abpp/battles/la002.htm>.

(3) Beauregard, G. T. “War of the Rebellion: Serial 011 Page 0451 Chapter XXII. CORRESPONDENCE,ETC.-CONFEDERATE., Special Orders, Hdqrs. Army of the Mississippi, No. 41, Corinth, April 26, 1862.” Ohio State University, Department of History, n.d. Web. 27 July 2016. <http://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/011/0451>.

(4) Stone, Kate. Brokenburn; the Journal of Kate Stone, 1861-1868. Ed. John Q. Anderson. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1955. Internet Archive. Web. 10 Aug. 2016. Page 108-109.<https://archive.org/stream/brokenburnthejou008676mbp#page/n137/mode/2up>.

(5) Inflation Calculator. http://www.westegg.com/inflation/ Accessed 10 Aug. 2016.

(6) Pinkston, Georgia Payne Durham. A Place to Remember: East Carroll Parish, LA 1832-1976. Baton Rouge: Claitor’s Publishing Division. 1977. Page 259.

(7) “United States Census, 1860”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MFPQ-LXX : 30 December 2015), James D Kerr, 1860.

(8) Ancestry.com. 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. M653, 1,438 rolls. James D. Kerr, Carroll Parish, Louisiana. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

(9) “Personal” Arkansas Gazette, June 5, 1890, page 5. Accessed 27 July 2016 via Genealogy Bank.

(10) “City News” Arkansas Gazette, June 14, 1890, page 3. Accessed 27 July 2016 via Genealogy Bank.